, ISLAMIC BYZANTIUM, 1453-1922, Era of Diocletian 1170-1639, 469

years

V. FIFTH EMPIRE,

OTTOMANS

V. FIFTH EMPIRE,

OTTOMANS

| Osmanli Oghullarļ | |

|---|---|

| 'Osman I | 1290-1326 |

| defeats Romans near

Nicomedia, Ottoman conquest begins, 1302; Seljuks overthrown, 1307; Bursa [Prusa] taken, 1326 | |

| Orkhān | 1326-1359 |

| defeats Andronicus III, 1329; I.znik [Nicaea] taken, 1331; I.zmid [Nicomedia] taken, 1337; Gelibolu [Kallipolis] taken, 1354; Ankara [Angora] taken, 1354 | |

| Murād I | 1359-1389 |

| Edirne [Adrianople] taken, 1369; Konya [Iconium] taken, 1387; Thessalonica taken, 1387; battle of Kosovo, "Field of the Blackbirds," Sult.ān killed defeating Serbs, 1389 | |

| Bāyezīd I Yļldļrļm, the "Thunderbolt" |

1389-1402 |

| seige of Constantinople, 1394-1402; Battle of Nicopolis, Sigismund of Hungary defeated, 1396; Battle of Ankara, Sult.ān defeated, captured & imprisoned by Tamerlane, 1402 | |

| Meh.med I | 1402-1421 |

| Civil War, 1402-1413, between Meh.med, Süleymān, & Mūsā; Thessalonica ceded to Romania, 1403 | |

| Murād II | 1421-1451 |

| Seige of Constantinople, 1422; Thessalonica captured from Venice, 1430 | |

| Meh.med II Fātih. the "Conqueror" | 1451-1481 |

| I.stanbul [Constantinople] taken, 1453; conquest of Bosnia, 1463; Khanate of Crimea becomes a Vassal, 1475; Seige of Rhodes repulsed, 1480 | |

| Bāyezīd II | 1481-1512 |

| Selīm I Yavuz, "the Grim" |

1512-1520 |

| Conquest of Syria and Egypt, 1516-1517 | |

| Süleymān I, the Magnificent | 1520-1566 |

| Fall of Rhodes, 1523; Battle of Mohįcs, Conquest of Hungary, death of Louis II of Hungary & Bohemia, 1526; First Siege of Vienna, 1529; Conquest of Mesopotamia, 1534; Appeal arrives from Sult.ān of Acheh for aid against the Portuguese, 1563; Siege of Malta, 1565 | |

| Selīm II | 1566-1574 |

| Peace of Adrianople, tribute from Austria, 1568; conquest of Cyprus, 1571; Battle of Lepanto, naval defeat by Spain, Venice, & Malta, 1571 | |

| Murād III | 1574-1595 |

| inconclusive war with Austria, 1593-1606 | |

| Meh.med III | 1595-1603 |

| Ah.med I | 1603-1617 |

| Mus.t.afā I | 1617-1618 |

| 'Osmān II | 1618-1622 |

| Ah.med I (restored) | 1622-1623 |

| Murād IV | 1623-1640 |

| Ibrāhīm | 1640-1648 |

| Meh.med IV | 1648-1687 |

| Naval defeat by Venice & Malta at Dardanelles, 1656; War with Austria, 1663-1664; Conquest of Crete from Venice, 1669; Second Siege of Vienna, 1683; Austrian conquest of Hungary, 1686-1697 | |

| Süleymān II | 1687-1691 |

| Parthenon destroyed in explosion, 1687 | |

| Ah.med II | 1691-1695 |

| Mus.t.afā II | 1695-1703 |

| Russia takes Azov, 1696; Loss of Hungary, 1697; Peace of Karolwitz, 1699 | |

| Ah.med III | 1703-1730 |

| Recovery of Azov, 1711; War with Austria, 1716-1718; Loss of Banat, Serbia, & Little Wallachia, 1716-1718; Peace of Passarowitz, 1718 | |

| Mah.mud I | 1730-1754 |

| War with Austria, Recovery of Serbia & Wallachia, 1737-1739; Peace of Belgrade, 1739 | |

| 'Osmān III | 1754-1757 |

| Mus.t.afā III | 1757-1774 |

| 'Abdül-H.amīd I | 1774-1789 |

| Russian conquest of Crimea, 1774-1783 | |

| Selīm III | 1789-1807 |

| Odessa annexed by Russia, 1791; Revolt of Serbs, 1804-1813; Russian invasion, occupation of Moldavia & Wallachia, 1806-1812; Sult.ān overthrown by Janissaries, 1807 | |

| Mus.t.afā IV | 1807-1808 |

| Mah.mūd II | 1808-1839 |

| Treaty of Bucharest, Russia ceded Bessarabia, 1812; Serbian autonomy, 1813; Greek Revolt, 1821-1829; Sult.ān massacres Janissaries, 1826; Russian invasion, occupation of Moldavia & Wallachia, 1828-1829; Treaty of Adrianople, Greek Independence, Danube Delta to Russia, autonomy of Moldavia & Wallachia, 1829 | |

| 'Abdül-Mejīd I | 1839-1861 |

| Crimean War, 1853-1856; Russian invasion, 1853; Britain, France, & Austria enter against Russia, 1854; Austria occupies Moldavia & Wallachia, 1854-1857; Siege of Sebastopol, 1854-1855; Peace of Paris, recovery of Danube Delta, Wallachia & Moldavia combined as Romania, with part of Bessarabia, 1856 | |

| 'Abdül-'Azīz | 1861-1876 |

| Revolts in Bosnia & Bulgaria, 1875-1876 | |

| Murād V | 1876 |

| 'Abdül-H.amīd II, "the Damned" | 1876-1909 |

| Russo-Turkish War, 1877-1878; Congress of Berlin, Serbia, Romania, & Montenegro Independent, Bulgaria autonomous, Bessarabia to Russia, Dobruja to Romania, Cyprus to Britain, Bosnia, Herzegovina & Novipazar, Austrian Protectorate, 1878; British Occupy Egypt, 1882; Bulgaria annexes East Rumelia, 1885; Revolt of the Young Turks, 1908, Sult.ān overthrown | |

| Meh.med V | 1909-1918 |

| First Balkan War, 1912-1913; Italy occupies Libya & the Dodecanese, 1912; Second Balkan War, recovery of Adrianople, 1913; World War I, 1914-1918 | |

| Meh.med VI | 1918-1922 |

| Armenian Republic conquered, 1920-1921; Greco-Turkish War, 1920-1922 | |

| 'Abdül-Mejīd II | Caliph only, 1922-1924 |

The historical and international image of the Turks does not seem to be the

most lovable or romantic. Most Americans probably are going to be more

sympathetic to people with historic grievances against Turkey -- Greeks,

Armenians, Romanians, Serbs, even Arabs.  The disappearance of all the ancient peoples of Anatolia, from the

Phrygians and Galatians to the Isaurians, and the sad Fall of Constantinople,

now combines with lingering outrage over the genocide of the Armenians

during World War I -- an event that Turkey still officially

and stoutly denies, despite thorough historical documentation,

not to mention many surviving eyewitnesses -- and more recent actions against

the Kurds. Not long ago it was a crime in Turkey to assert, even on the floor of

the parliament, that there even were Kurds in the country -- and in 1994

four members of parliament were sentenced to 15 years in prison for

giving speeches in Kurdish. Although responding in some ways to European demands

for human rights improvements before being considered for admission to the

European Union, since December 2001 the Turkish government has officially

regarded Kurdish given names as "terrorist propaganda" and refused to register

them for Kurdish children. With all this, one does not even need to see the very

hostile, anti-Turkish movie Midnight Express [1978].

The disappearance of all the ancient peoples of Anatolia, from the

Phrygians and Galatians to the Isaurians, and the sad Fall of Constantinople,

now combines with lingering outrage over the genocide of the Armenians

during World War I -- an event that Turkey still officially

and stoutly denies, despite thorough historical documentation,

not to mention many surviving eyewitnesses -- and more recent actions against

the Kurds. Not long ago it was a crime in Turkey to assert, even on the floor of

the parliament, that there even were Kurds in the country -- and in 1994

four members of parliament were sentenced to 15 years in prison for

giving speeches in Kurdish. Although responding in some ways to European demands

for human rights improvements before being considered for admission to the

European Union, since December 2001 the Turkish government has officially

regarded Kurdish given names as "terrorist propaganda" and refused to register

them for Kurdish children. With all this, one does not even need to see the very

hostile, anti-Turkish movie Midnight Express [1978].

In historical perspective, however, it is not clear to what extent the ancient peoples even still existed by the time of the Turkish arrival. Greek assimilation, i.e. Hellenization, of Anatolian peoples had been progressing steadily for centuries, and Turkish settlement in comparison doesn't necessarily look all that different. Given the religious cause that they thought they were vindicating (for which Islām usually seems more excused than Christianity), the Fall of Constantinople, far from sad, was one of the supreme moments of achievement in the history of Islām. A Western, or a modern liberal, evaluation will not give that much weight, but it is not hard to imagine that the sensation it created in Islām was not much different from that in Christendom at the capture of Jerusalem by the First Crusade, or the completion of the Reconquista in Spain. These are similarly denigrated by modern opinion, but it is hard to imagine how the values at the time could have been different -- everyone should guard against an anachronistic indignation.

The subsequent Ottoman Empire features the goods and evils characteristic of most empires, and some peculiar to those of the Middle East -- e.g. the refuge provided for Spanish Jews in 1492, as against the slavery and forced conversion of Christian children for the Janissary corps. Evils specific to nationalism emerged later, like the aforementioned genocide of Armenians and the continuing suppression of the Kurds, an Iranian people who happen to be Orthodox Moslems like the Turks. The Turks are not uniquely at fault for this, and the solution is a kind of society (liberal and capitalistic) upon which few in the world entirely agree, even in the ethnic plurality of societies like the United States. Turkey now has an especially tough time with its own identity as it is torn between the Islamic fundamentalist revival seen elsewhere and the secularism that Kemal Atatürk made the foundation of the modern state in the 1920's. None of this may make Turkey particularly lovable, but it does make the Turks mostly like anybody else, with a history that has its horrors but, indeed, also its own bit of romance and magnificience: a desire to surpass Sancta Sophia (still called Aya Sofya in Turkish, after the Greek version of the name, Hagia Sophia) produced a series of some of the most beautiful mosques in Islām, which have inspired much of subsequent Islāmic architecture (the standard doomed mosque, starting with Muh.ammad 'Alī's Alabaster Mosque in Cairo) [note].

Today one of the sights of Istanbul is the Fatih Camii (Fātih.

Jāmi-i), the "Conqueror's Mosque." This contains the tomb of Meh.med II,

with a dedicated mosque, school, hospice, and (formerly) caravansaray. It stands

on the site of the Church of the Holy Apostles, which was the burial place of

the Emperor Constantine and

subsequent Emperors of Romania. Already largely in ruins in 1453, it is not

clear what the fate of all the Imperial burials was -- they may actually have

simply been covered over by the later construction, the way the Imperial mosaics

in Sancta Sophia were simply whitewashed, preserving them for modern display. A

great deal of Roman Constantinople actually survives underground and invisible

in modern Istanbul. What the Church of the Holy Apostles probably looked like

can still be seen in a probable copy, St. Mark's in Venice.

At Meh.med II's death, the Ottoman Empire looked much the way

Romania had in the 11th Century. Selīm I "the Grim" did what the old Emperors

had never been able to do, restore Syria and Egypt to the empire (from the Mamlūks). Süleimān I then

added areas that had never been permanent parts of the Roman Empire, Iraq and

Hungary. Picking up the Roman conflict with Irān, the Turks for the

first time since Alexander

the Great removed Iraq from Iranian possession (the map shows the pre-Safavid Aq Qoyunlu or White Sheep Turks). The

conquest of Hungary

was the first penetration of Islām into Francia since the conquest of Spain.

At Meh.med II's death, the Ottoman Empire looked much the way

Romania had in the 11th Century. Selīm I "the Grim" did what the old Emperors

had never been able to do, restore Syria and Egypt to the empire (from the Mamlūks). Süleimān I then

added areas that had never been permanent parts of the Roman Empire, Iraq and

Hungary. Picking up the Roman conflict with Irān, the Turks for the

first time since Alexander

the Great removed Iraq from Iranian possession (the map shows the pre-Safavid Aq Qoyunlu or White Sheep Turks). The

conquest of Hungary

was the first penetration of Islām into Francia since the conquest of Spain.

The Ottoman Empire was at its height for about 150 years. It had at

that point, however, reached the limits beyond which it could not easily project

its power. Conflict continued with Austria and with Christian powers in the

Mediterranean, but respective holdings didn't change much. The Sult.ān Ah.mad

Mosque, or the Blue Mosque, adjacent to the site of the old Hippodrome of

Constantinople, is a fitting symbol of the achievement and confidence of this

period. The long delayed fall of Crete in 1669 then seemed like the portent of

renewed conquests. The energetic Köprülü vizirs planned a new assault, after 150

years, against Vienna in 1683. But this turned into a disaster, suddenly

revealing the relative weakness that had actually overcome the Empire. Even a

de facto alliance with friendly France, the greatest power of the day,

could not prevent a series of defeats, the loss of Hungary, and the temporary

loss of southern Greece to Venice.

The Ottoman Empire was at its height for about 150 years. It had at

that point, however, reached the limits beyond which it could not easily project

its power. Conflict continued with Austria and with Christian powers in the

Mediterranean, but respective holdings didn't change much. The Sult.ān Ah.mad

Mosque, or the Blue Mosque, adjacent to the site of the old Hippodrome of

Constantinople, is a fitting symbol of the achievement and confidence of this

period. The long delayed fall of Crete in 1669 then seemed like the portent of

renewed conquests. The energetic Köprülü vizirs planned a new assault, after 150

years, against Vienna in 1683. But this turned into a disaster, suddenly

revealing the relative weakness that had actually overcome the Empire. Even a

de facto alliance with friendly France, the greatest power of the day,

could not prevent a series of defeats, the loss of Hungary, and the temporary

loss of southern Greece to Venice.

It is noteworthy at this point that Ottoman Sult.āns ceased to murder their

brothers on accession. Henceforth the Throne passes, by Middle Eastern custom,

to brothers and even to cousins before going to the next generation.

The threat of continuous defeat, which the beginning of the 18th century

seemed to display, receded somewhat. Austria would not advance deeper into the

Balkans and there was some breathing room. Nevertheless, the Ottomans were now

facing the problem of catching up with the technological advances of Europe,

even of relatively backward Russia, which it was in no way prepared to tackle.

The problem was not any particular hostility to modern commercial culture --

merchants and markets were perfectly respectable characteristics of Middle

Eastern Islāmic civilization -- but a very profound social conservativism, a

satisfaction with the Mediaeval forms of life, prevented any of this from

developing into modern institutions of banking, industry, and entrepreneurship.

Like the Chinese, the Turks literally did not believe there was anything new to

learn, much less from despised Unbelievers. The bustle and excitement of the

great Istanbul Bazaar thus never led to the explosion of energy and production

that was already characteristic of the Netherlands and other places in Western

Europe. Turkey would always be playing catch-up but would then never actually

catch up. Institutional reforms, when they were even tried, still could never go

deep enough, could never actually produce a people striving and inquisitive

beyond their previous habits. Peter the Great faced

similar problems with another conservative society about the same time.

At the beginning of the 19th century, as Napoleon surged back and forth across Europe, the subject Christians of the Balkans became more and more restless, and Russia began to try again and again to retrieve Constantinople for Christendom and break through the Straits. The Ottomans, although achieving some successes, were not going to be able to resist this. The Empire's status as the "Sick Man of Europe" was now becoming quite established. It was Realpolitik that came to the rescue of the Sult.ān: Britain did not want Russia to be too successful and so entered into a long policy of supporting the Turks against the forces, from Russia or Egypt or wherever, that might result in the collapse of Ottoman rule. Nevertheless, Britain could not allow too much oppression of subject Christians, and as the century wore on, small Christian states, from Serbia to Greece to Bulgaria, were allowed autonomy and then independence by the agreement of the Great Powers. This did not get any of them all they wanted, and it certainly limited Russian gains, but it kept the geo-political dam from bursting and kept the Sult.ān from falling off his Throne.

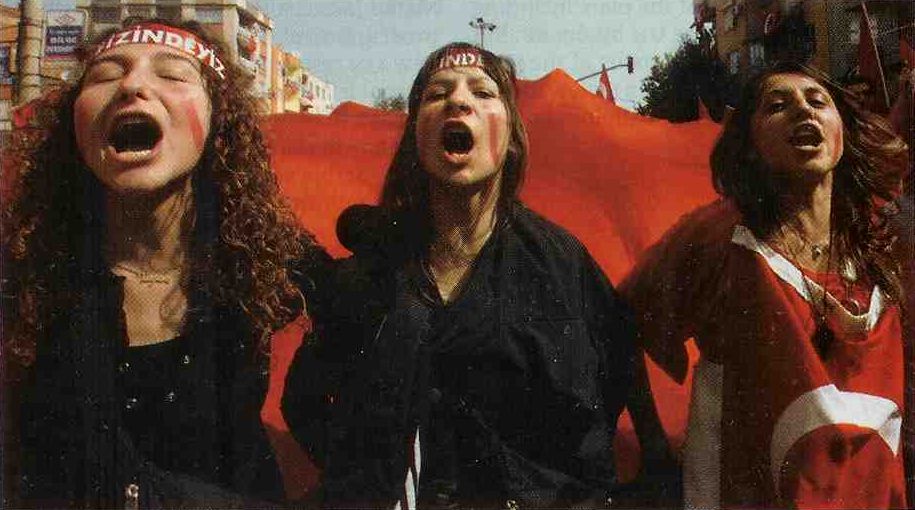

Finally, it was the internal forces of Turkey that began to shake things up

after a pattern that would become all too familiar in "underdeveloped" countries

later: A military coup, the "Young Turks," against the detested Sult.ān

'Abdül-Hamīd II in 1908.  This did not help much when the Balkan states fell on Turkey in

1912. The choice of Germany as a European ally would then be fatal for the

Ottoman future. Another ill effect was the transformation of the Mediaeval Cause

of Islām into a more modern Turkish nationalism. This did not work well, and

never would, with the Arabs, Armenians, and Kurds living within Turkish borders.

The disaffection of the first exploded in a pro-Allied revolt in World War I.

Suspicion about the second led to shameful deportation and massacre about the

same time. And conflict with the third continues, with campaigns of terrorism

and suppression, even today. Woodrow Wilson impotently

called for an independent Armenia state, in an area where there were by then few

Armenians left, and soon almost none after Turkey pushed the Armenian Republic

back east of the Araks (Aras) River in 1920. No Power has called for an

independent Kurdish state. Meanwhile, the British and French were perfectly

happy to detach the Arab lands from the Empire, not for independence, to be

sure, but to further British and French imperial projects. This turned out to be

more trouble than it was worth, especially when the Zionist colonization of

Palestine, allowed by the British, led to the creation of Israel and to a conflict,

including five major wars (1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, 1982), that continues until

today. The settlement of World War I has thus been aptly called "the peace to

end all peace."

This did not help much when the Balkan states fell on Turkey in

1912. The choice of Germany as a European ally would then be fatal for the

Ottoman future. Another ill effect was the transformation of the Mediaeval Cause

of Islām into a more modern Turkish nationalism. This did not work well, and

never would, with the Arabs, Armenians, and Kurds living within Turkish borders.

The disaffection of the first exploded in a pro-Allied revolt in World War I.

Suspicion about the second led to shameful deportation and massacre about the

same time. And conflict with the third continues, with campaigns of terrorism

and suppression, even today. Woodrow Wilson impotently

called for an independent Armenia state, in an area where there were by then few

Armenians left, and soon almost none after Turkey pushed the Armenian Republic

back east of the Araks (Aras) River in 1920. No Power has called for an

independent Kurdish state. Meanwhile, the British and French were perfectly

happy to detach the Arab lands from the Empire, not for independence, to be

sure, but to further British and French imperial projects. This turned out to be

more trouble than it was worth, especially when the Zionist colonization of

Palestine, allowed by the British, led to the creation of Israel and to a conflict,

including five major wars (1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, 1982), that continues until

today. The settlement of World War I has thus been aptly called "the peace to

end all peace."

The

spelling of the names of the Ottomans is intended to indicate both the Turkish

pronunciation and how they are spelled in Arabic (which no longer matters, since

Turkish is no longer written in the Arabic alphabet, but is of historical

interest). Here I have pretty much followed the usage of the Cambridge

History of Islam. A good example is the name of the Conqueror of

Constantinople, Meh.med II. This name is Muh.ammad in Arabic but

is actually pronounced Mehmet in Turkish. Obviously, some compromises are

made and the system is not perfect. In general, the consonants look Arabic and

the vowels Turkish. Since Turkish (and Persian) reads the Arabic alphabet with

three s's (Arabic s, s., and th) and four z's

(Arabic z, z., d., and dh), some attempt is made to

differentiate (e.g. with s for th). Modern Turkish writes

c for English j and ē for English ch, but the

English equivalents are used here.

The main reason that Arabic writing did not work well for Turkish was the

Turkish vowel system. Where Classical Arabic  had three short and three long vowels, and Persian

had three short and three long vowels, and Persian  could match its six vowels with those, Turkish has eight vowels, as

shown at left (in the official Romanization). The most intriguing thing about

Turkish vowels is the system of vowel harmony. Related Ural-Altaic

languages, like Mongolian and

even Hungarian

(though some dispute the reality of the Ural-Altaic family, or even the Altaic

family, or whether Korean and Japanese are Altaic

members), also have vowel harmony, but this seems to appear in Turkish in its

most complete, logical, and elegant form. The rules are simply, (1) front vowels

are followed by front vowels (e.g. i by e), back vowels by back vowels (e.g. u

by a), (2) unrounded vowels are followed by unrounded vowels (e.g. i by e), and

(3) rounded vowels are followed by high rounded (e.g. o by u) or low unrounded

vowels (e.g. o by a). There are Turkish grammatical inflections in which the

vowel is supposed to be simply either high or low, with its character otherwise

determined by the preceding vowels in the word. This all was impossible to show

in the Arabic alphabet without a special notation that might have been developed

but, evidently, never was. There are many words in Turkish that violate vowel

harmony, but by this they can be identified as foreign loan words -- for example

islām (instead of *islem), from Arabic, and istanbul

(instead of *istenbil), from Greek or Arabic.

could match its six vowels with those, Turkish has eight vowels, as

shown at left (in the official Romanization). The most intriguing thing about

Turkish vowels is the system of vowel harmony. Related Ural-Altaic

languages, like Mongolian and

even Hungarian

(though some dispute the reality of the Ural-Altaic family, or even the Altaic

family, or whether Korean and Japanese are Altaic

members), also have vowel harmony, but this seems to appear in Turkish in its

most complete, logical, and elegant form. The rules are simply, (1) front vowels

are followed by front vowels (e.g. i by e), back vowels by back vowels (e.g. u

by a), (2) unrounded vowels are followed by unrounded vowels (e.g. i by e), and

(3) rounded vowels are followed by high rounded (e.g. o by u) or low unrounded

vowels (e.g. o by a). There are Turkish grammatical inflections in which the

vowel is supposed to be simply either high or low, with its character otherwise

determined by the preceding vowels in the word. This all was impossible to show

in the Arabic alphabet without a special notation that might have been developed

but, evidently, never was. There are many words in Turkish that violate vowel

harmony, but by this they can be identified as foreign loan words -- for example

islām (instead of *islem), from Arabic, and istanbul

(instead of *istenbil), from Greek or Arabic.

In the first book I had about Turkish, Teach Yourself Books, Turkish

[St. Paul's House, Warwick Lane, London, 1953, 1975], the author, G.L. Lewis,

specifically ridicules Hagopian's Ottoman-Turkish Conversation-Grammar of

1907 because, out of 215 pages, it  devoted 161 to Arabic and Persian [p.vi]. Well, I have gone to some

trouble to get a copy of Hagopian's Ottoman-Turkish Conversation-Grammar,

and it is a very fine book. The section on Arabic and Persian is very much as

though every English grammar book came along with Donald M. Ayers' English

words from Latin and Greek elements [University of Arizona Press, 1986],

which I encountered as the textbook for a popular class at the University of

Texas on the Greek and Latin contributions to English. As it happens, of course,

fewer and fewer American students are even taught English grammar, much

less enough Greek or Latin to understand or appreciate its use of them. This not

a virtue. Nor is the nationalistic enthusiasm that seeks to purge languages of

"foreign" words, which has happened in Turkish, German, French, Hungarian, and

elsewhere. This kind of thing is simply an attempt to purge history itself --

along with a ugly attempt to sharpen ethnic identities and differences.

devoted 161 to Arabic and Persian [p.vi]. Well, I have gone to some

trouble to get a copy of Hagopian's Ottoman-Turkish Conversation-Grammar,

and it is a very fine book. The section on Arabic and Persian is very much as

though every English grammar book came along with Donald M. Ayers' English

words from Latin and Greek elements [University of Arizona Press, 1986],

which I encountered as the textbook for a popular class at the University of

Texas on the Greek and Latin contributions to English. As it happens, of course,

fewer and fewer American students are even taught English grammar, much

less enough Greek or Latin to understand or appreciate its use of them. This not

a virtue. Nor is the nationalistic enthusiasm that seeks to purge languages of

"foreign" words, which has happened in Turkish, German, French, Hungarian, and

elsewhere. This kind of thing is simply an attempt to purge history itself --

along with a ugly attempt to sharpen ethnic identities and differences.

Later, Geoffrey Lewis appears to have thought better of his ridicule. Subsequently editions of Teach Yourself Turkish cut down on the dismissive remarks; and recently Lewis has published The Turkish Language Reform, A Catastrophic Success [Oxford, 1999, 2002]. Here we learn about the artificial coinages, supposedly "true" Turkish, and the confusion that has now alienated modern Turkey from its own heritage, the best of Ottoman literature. Indeed, the writings of Kemal Atatürk himself have needed more than once to be "translated" into New(er) Turkish. At a literary or technical level usage still sometimes shifts between an Arabic word, a "Turkish" neologism, or French, just to make sure that everyone can recognize one of the words. Lewis's own Turkish Grammar [Oxford, 1967, 2000] provides information to enable people to read the Ottoman language. It probably is too late to deliberately go back, but, like German returning to Telefon from Fernsprecher, perhaps Turkish usage will drift back to more of its Persian and Arabic heritage.

| Turkish Republic, 1923; Presidents | |

|---|---|

| Mustafa Kemal, (1934) Atatürk |

1923-1938 |

| Ismet Inönü | 1938-1950 |

| France cedes Alexandretta & Antioch, 1939 | |

| Celal Bayar | 1950-1960 |

| Kemal Gürcel | 1961-1966 |

| Cevdet Sunay | 1966-1973 |

| Fahri Korutürk | 1973-1980 |

| Kenan Evren | 1980-1989 |

| Turgut Özal | 1989-1993 |

| Süleyman Demirel | 1993-2000 |

| Ahmet Necdet Sezer | 2000-2007 |

| Abdullah Gül | 2007 |

who adopted the surname Atatürk, "Father of the Turks." With no

concessions to Greeks, Armenians, or Kurds, Atatürk nevertheless abandoned most

imperial aspirations. Giving up the Arabic alphabet and traditional costume

(indeed, making their use even a capital offense), deposing the Ottomans, and

otherwise trying to make Turkey a European, rather than a Middle Eastern, state,

Atatürk simply hoped to make it the equal of other modern powers. To a

considerable extent he succeeded, though Turkey is still haunted by the shadow

of the military dictatorship that he himself represented, by the threat of

militant Islām, whose mediaevalism is fully triumphant in neighboring Irān, and

by the disaffection of the Kurds, whose very existence was legally denied for

many years. Nevertheless, it is undoubtedly the strongest state in the region,

to the chagrin of neighboring Arabs and Christians alike. Long a member of NATO,

Turkey looks foward to membership in the European Community, but still has

little embarrassments like the common use of torture by police. Thus, despite

Atatürk, we still have several respects in which Turkey is posed between East

and West, Mediaeval and Modern, Islām and secularism, liberalism and oppression.

The application of Turkey to the European Union has been defered, but will be

considered in a couple of years.

who adopted the surname Atatürk, "Father of the Turks." With no

concessions to Greeks, Armenians, or Kurds, Atatürk nevertheless abandoned most

imperial aspirations. Giving up the Arabic alphabet and traditional costume

(indeed, making their use even a capital offense), deposing the Ottomans, and

otherwise trying to make Turkey a European, rather than a Middle Eastern, state,

Atatürk simply hoped to make it the equal of other modern powers. To a

considerable extent he succeeded, though Turkey is still haunted by the shadow

of the military dictatorship that he himself represented, by the threat of

militant Islām, whose mediaevalism is fully triumphant in neighboring Irān, and

by the disaffection of the Kurds, whose very existence was legally denied for

many years. Nevertheless, it is undoubtedly the strongest state in the region,

to the chagrin of neighboring Arabs and Christians alike. Long a member of NATO,

Turkey looks foward to membership in the European Community, but still has

little embarrassments like the common use of torture by police. Thus, despite

Atatürk, we still have several respects in which Turkey is posed between East

and West, Mediaeval and Modern, Islām and secularism, liberalism and oppression.

The application of Turkey to the European Union has been defered, but will be

considered in a couple of years.The term of Turkish President Ahmet Necdet Sezer ended on 16 May 2007, but a

new President was not elected until August. The most likely candidate and

eventual President, Abdullah Gül, from an Islamic Party  (and with a wife who wears a headscarf), drew wide protest

from everyone who wished to preserve the secular nature of the Turkish Republic.

There was even a warning from the Army, which has deposed the government four

times since 1960, that it may not tolerate any compromise to Atatürk's ideal of

secular government. The Islamic threat would seem to justify the reluctance of

the European Union to expedite the admission of Turkey, an attitude that some

Turks regard as simple racism. However, the defeat of the Islamic forces in

Turkey should remove some European reservations. The actual election of Gül

leaves all these issues rather up in the air.

(and with a wife who wears a headscarf), drew wide protest

from everyone who wished to preserve the secular nature of the Turkish Republic.

There was even a warning from the Army, which has deposed the government four

times since 1960, that it may not tolerate any compromise to Atatürk's ideal of

secular government. The Islamic threat would seem to justify the reluctance of

the European Union to expedite the admission of Turkey, an attitude that some

Turks regard as simple racism. However, the defeat of the Islamic forces in

Turkey should remove some European reservations. The actual election of Gül

leaves all these issues rather up in the air.

A discussion of general sources for this material is given under Francia and Islām. Some additional sources

include The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia (John Channon with Rob

Hudson, 1995), and various prose histories, such as The Ottoman Centuries

(Lord Kinross, Morrow Quill, 1977).

The Shihābī Amīrs of Lebanon, 1697-1842 AD

The House of Muh.ammad 'Alī in Egypt, 1805-1953 AD

The Sanūsī Amīrs & Kings of Libya, 1837-1969 AD

Not all who deny the existence of the Armenian genocide are Turkish, as I learned from e-mail recently. Anyone sincerely sceptical or confused about the matter should consult Death by Government (Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1995, pp.209-239), by R.J. Rummel, one of the greatest living experts on mass murder. Rummel estimates the number of Armenians murdered in the main organized genocide program (there were others), from 1915-1918, as 1,404,000 persons. Some of the eyewitness testimony to this included reports by the American Ambassador to Turkey, Henry Morgenthau, Sr. (whose son, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., would be Franklin Roosevelt's Secretary of the Treasury), and by other American consular officials, at a time when the United States was still neutral in World War I. Morgenthau's account was published in 1919 as Ambassador Morgenthau's Story.

Nor should we disparage the endless pornographic fantasies that revolve

around the Harīm of the Sult.ān's Topkapļ Palace.  Fascination with this is now often disparaged as "Orientalism," i.e.

the projection of unrelated and hostile imaginings onto misunderstood

institutions; but there is no doubt of the extraordinary and bizarre

characteristics of the Imperial Harīm. If it was diverting for the Sult.ān, I

don't see why it should not continue to be so to the curious modern. An honest

and informed treatment of this can be found in Harem, The World Behind the

Veil [Abbeville Press, New York, London, Paris, 1989], by a woman who grew

up in Turkey, Alev Lytle Croutier, many of whose own relatives had lived in

traditional harīms. The books contains photographs from the Ottoman era

(including her relatives) as well as historical drawings and the sort of lush

and sensual paintings by Western artists that infuriate the anti-"Orientalism"

crowd. The image above is a 19th century photograph. It is given by Croutier

[p.74], but I also remember it from many years ago in Time magazine, at

the time that the Topkapļ Harīm was first opened to the public.

Fascination with this is now often disparaged as "Orientalism," i.e.

the projection of unrelated and hostile imaginings onto misunderstood

institutions; but there is no doubt of the extraordinary and bizarre

characteristics of the Imperial Harīm. If it was diverting for the Sult.ān, I

don't see why it should not continue to be so to the curious modern. An honest

and informed treatment of this can be found in Harem, The World Behind the

Veil [Abbeville Press, New York, London, Paris, 1989], by a woman who grew

up in Turkey, Alev Lytle Croutier, many of whose own relatives had lived in

traditional harīms. The books contains photographs from the Ottoman era

(including her relatives) as well as historical drawings and the sort of lush

and sensual paintings by Western artists that infuriate the anti-"Orientalism"

crowd. The image above is a 19th century photograph. It is given by Croutier

[p.74], but I also remember it from many years ago in Time magazine, at

the time that the Topkapļ Harīm was first opened to the public.

| The Shihābī Amīrs of Lebanon | |

|---|---|

| Bashīr I | 1697-1707 |

| H.aydar | 1707-1732 |

| Mulh.im | 1732-1754 |

| Mans.ūr | 1754-1770 |

| Yūsuf | 1770-1788 |

| first Maronite Amīr, 1770 | |

| Bashīr II | 1788-1840 |

| overthrown by Britain & Turkey, 1840 | |

| Bashīr III | 1840-1842 |

| direct Turkish Rule, 1842-1918; French Rule, 1920-1943 | |

| Republic of Lebanon | |

| Bishara al-Khuri | President, 1943-1952 |

| Camille Chamoun | 1952-1958 |

| Fuad Chehab | 1958-1964 |

| Charles Hélou | 1964-1970 |

| Sulayman Franjieh | 1970-1976 |

| Elias Sarkis | 1976-1982 |

| Amin Gemayel | 1982-1988 |

| Selim al-Huss | 1988-1989 |

| Elias Hrawi | 1989-1998 |

| Émile Lahoud | 1998-present |

The Israelis, who invaded Lebanon in 1982 to get rid of the

Palestinians, more or less accomplished that task, with the PLO leaving for

Tunisia, but then discovered, as the Syrians had already, that the communal

rivalries of the Lebanese themselves, especially with the Shi'tes adopting

Iranian suicide and terror tactics, made the place a tar baby for any outsiders

who wanted to exert control by force. With the foreign powers chasened, the

Lebanese began to patch things up with some needed political compromises; and as

the 1990's progressed, some peace and prosperity seemed to be returning to the

country. It remains to be seen, however, if a modus vivendi can be found

to produce another golden age of communal alliance against the outside.

The Israelis, who invaded Lebanon in 1982 to get rid of the

Palestinians, more or less accomplished that task, with the PLO leaving for

Tunisia, but then discovered, as the Syrians had already, that the communal

rivalries of the Lebanese themselves, especially with the Shi'tes adopting

Iranian suicide and terror tactics, made the place a tar baby for any outsiders

who wanted to exert control by force. With the foreign powers chasened, the

Lebanese began to patch things up with some needed political compromises; and as

the 1990's progressed, some peace and prosperity seemed to be returning to the

country. It remains to be seen, however, if a modus vivendi can be found

to produce another golden age of communal alliance against the outside.

Maronite Patriarchs of Lebanon

Egypt was abruptly pulled into modern history with the invasion of Napoleon in 1798. Although Egypt had been conquered by the Turks in 1517, the strange slave dynasty of the Mamlūks had continued and by Napoleon's time had reestablished de facto authority in the declining Empire. After the French were driven from Egypt in 1801, Muh.ammad 'Alī arrived, supposedly to reėstablish Turkish authority.

Brilliant, ruthless, farsighted, and probably the most important Albanian in world history, Muh.ammad 'Alī very quickly established his own authority instead. The final Mamlūks were massacred in 1811, and Muh.ammad 'Alī moved to create a modern state, and especially a modern army, for Egypt. In this he was as successful as any non-European power at the time. By the time the Greeks revolted against Turkey in 1821, it was Muh.ammad 'Alī who turned out to have the best resources to put down the revolution and was called on by the Sult.ān in 1824 to do so. He very nearly did, until Britain intervened and sank the Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Navarino in 1827. Frustrated in that direction, Muh.ammad 'Alī was successful in his conquest of the Sudan (1820-1822), probably advancing further up the Nile than any power since Ancient Egypt, though at a terrible cost to the Sudanese in massacre, mutilations, and slaving (of which the American boxer Cassius Clay was probably unaware when he adoped the name "Muhammad Ali" upon his conversion to Islām). Egyptian interventions in Arabia in 1818-1822 and 1838-1843 very nearly exterminated the House of Sa'ūd and its fundamentalist Wahhābī movement, which much later would create a united and independent Sa'ūdī Arabia.

| The House of Muh.ammad 'Alī in Egypt | |

|---|---|

| Muh.ammad 'Alī | Pasha, 1805-1848 |

| Ibrāhīm | 1848 |

| 'Abbās H.ilmī I | 1848-1854 |

| Muh.ammad Sa'īd | 1854-1863 |

| Suez Canal Started, 1859 | |

| Ismā'īl | 1863-1867 |

| Khedive, 1867-1879, d. 1895 | |

| Suez Canal Opened, 1869 Britain buys Khedive's share in Canal, 1875 | |

| Muh.ammad Tawfīq | 1879-1892 |

| British Occupation, 1882 | |

| 'Abbās H.ilmī II | 1892-1914, d. 1944 |

| British Protectorate, 1914-1922 | |

| H.usayn Kāmil | Sult.ān, 1914-1917 |

| Ah.mad Fu'ād I | 1917-1922 |

| King, 1922-1936 | |

| Fārūq | 1936-1952, d. 1965 |

| Ah.mad Fu'ād II | 1952-1953 |

| Republic of Egypt, 1953- | |

| Muhammad Naguib | President, 1953-1954 |

| Gamal Abdel Nasser | 1954-1970 |

| Anwar as-Sadat | 1970-1981 |

| Mohammed Hosni Mubarak |

1981-present |

The most formative subsequent event for Egyptian history was certainly the construction of the Suez Canal. Although Britain had nothing to do with the project, and it was the French Emperor Napoleon III who attended the lavish opening ceremonies, the collapse of Egyptian financies led to the purchase by Britain of all Egypt's shares in the Canal Company. This did not solve Egypt's financial problems, which got worse. The Khedive Ismā'īl also wasted resources on disastrous campaigns against Ethiopia in 1875-1876. With its interests now in danger, Britain occupied Egypt, without French support, in 1882. Ironically, the Occupation was undertaken under Prime Minister William Gladstone, who was opposed to British Imperialism. He was not, however, going to endanger British finances just because the Khedive didn't know how to handle his.

This made Egypt a de facto part of the British Empire, indeed one of the most important parts, with the Suez Canal an essential strategic link between Britain and India. Some of the most colorful episodes in British Imperial history occured because of this. In 1881 a revolt had started in the Sudan, led by a man claiming to be the Apocalyptic Mahdī of Islāmic tradition. Gladstone was not going to spend British money, or Egyptian, in trying to suppress the rebellion. Consequently, Charles Gordon, known as "Chinese Gordon" for his part in putting down the Taiping Rebellion in China (1860-1864), and who had already been governor-general of the Sudan from 1877-1880, was sent back in order to evacuate the Egyptian garrison. Once there, he decided to stay and resist the Mahdī. By 1885 this insubordination stirred up public opinion back home and forced Gladstone to send a relief expedition; but it missed rescuing Gordon by two days, as the Mahdī's forces overran Khartoum and killed Gordon. This made Gordon one of the great heroes of the day, humiliated Britain, and resulted in the fall of Gladstone's government. However, the Sudan was, for the time being, abandoned. When the British returned in 1898, in the heyday of imperial jingoism, Lord Kitchener, with a young Winston Churchill along, calmly massacred the mediaeval army of the Mahdī's successor at the Battle of Omdurman, avenged Gordon, and made himself one of the immortal heroes of the British Empire too. Although formally in Egyptian service, Kitchener reconquered the Sudan as an Anglo-Egyptian "condominium." The theory of British and Egyptian joint rule in the Sudan continued until Sudanese independence in 1956, though between 1924 and 1936 the British didn't even allow Egyptian forces or authorities into the Sudan.

All this took place with Egypt still legally part of the Ottoman

Empire. Right down until 1914 the Turkish flag was dutifully flown and Turkish

passports issued. When Turkey repaid a century of British support by throwing

its lot with Germany in World War I, however, the fiction came to an end, and

Egypt de jure came under British rule as a Protectorate, with the

Sult.ānate, abolished by the Turks in 1517, reėstablished. This was not

popular in Egypt, and after the war Egypt did become a formally independent

Kingdom. However, the British did retain Treaty rights to garrison and

protect the Suez Canal; so, in many ways, the British Occupation of 1882 simply

continued. There was little doubt of that once World War II started. Egypt, a

legally Neutral country, was first invaded by Italy and then by Germany, with

British forces meeting, fighting, and ultimately expelling them. Egypt at the

time seemed no less a part of the British Empire than it had ever been. Egypt

did eventually declare war on Germany, but not until February 24, 1945.

All this took place with Egypt still legally part of the Ottoman

Empire. Right down until 1914 the Turkish flag was dutifully flown and Turkish

passports issued. When Turkey repaid a century of British support by throwing

its lot with Germany in World War I, however, the fiction came to an end, and

Egypt de jure came under British rule as a Protectorate, with the

Sult.ānate, abolished by the Turks in 1517, reėstablished. This was not

popular in Egypt, and after the war Egypt did become a formally independent

Kingdom. However, the British did retain Treaty rights to garrison and

protect the Suez Canal; so, in many ways, the British Occupation of 1882 simply

continued. There was little doubt of that once World War II started. Egypt, a

legally Neutral country, was first invaded by Italy and then by Germany, with

British forces meeting, fighting, and ultimately expelling them. Egypt at the

time seemed no less a part of the British Empire than it had ever been. Egypt

did eventually declare war on Germany, but not until February 24, 1945.

The end of Muh.ammad 'Alī's dynasty resulted from the humiliation of

continuing British occupation, the mortification of Egyptian failure in the war

against Israeli independence in 1948, and from the failure of King Fārūq,

who was rather more successful as a playboy than as a leader, to deal with any

of it. The army, soon led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, swept away the monarchy,

got British forces to leave Egypt, and then won a great political victory when

Britain and France (74 years late) reoccupied the Canal, Israel invaded the

Sinai, and both the United States and the Soviet Union told them all to leave in

no uncertain terms, in the Suez Crisis of 1956 (just as Soviet tanks were

rolling into Hungary!). Thus, Egypt became a player in the Cold War, and

the heritage of Muh.ammad 'Alī, the Ottoman Empire, and British imperialism

faded rapidly.

| The Sanūsī Amīrs & Kings of Libya | |

|---|---|

| Muh.ammad as-Sanūsī | 1837-1859, Cyrenaica, 1841 |

| Muh.ammad al-Mahdī | 1859-1902 |

| Ah.mad ash-Sharīf | 1902-1916, d.1933 |

| Italian occupation, 1911 | |

| Muh.ammad Idrīs | 1916-1949; Amir, 1949-1951; King, 1951-1969, d.1983 |

| Muammar Qaddafi dictatorship, 1969-present | |

This was a thinly populated backwater for the Turks, noteworthy mainly for Roman ruins and piracy (with U.S. Marines landing at Tripoli in 1801). It all achieved greater significance when Italy displaced the Ottomans in 1911 (ceded in 1912). Indeed, Libya became one of the most important strategic theaters of World War II. The Italians tried invading Egypt from Libya in September 1940 but by February 1941 had been thrown completely out of Cyrenaica, with 130,000 soldiers captured. Alarmed, Hitler sent Erwin Rommel with a couple of divisions to prevent the Italian position from collapsing completely. Rommel, however, went on the offensive. For more than a year, things surged back and forth, with Cyrenaica recovered, lost, and recovered again. By July 1942, Rommel was deep into Egypt, barely stopped at El Alamein, 60 miles from Alexandria. By then, however, the United States was in the War; and the strongly reinforced British began an offensive in October. They broke through and soon swept the Germans and Italians entirely out of Libya. Retreating into Tunisia, they were caught against the Americans who had landed in Morocco and Algeria in November.

After the War, Libya formally became independent in 1951, under the Sasūnī

Amīr of Cyrenaica. The long lived King Idrīs was eventually overthrown in 1969.

This was under the leadership of the erratic and megalomaniacal Muammar Qaddafi.

Along with armed clashes with Egypt and Chad,  Libya became a sponsor of terrorism. Blamed for a bombing in Berlin

in 1986, Libya was bombed by Ronald Reagan in retaliation.

Later blamed for a bomb that brought down Pam Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie,

Scotland in 1988, sanctions were imposed on Libya until accused operatives were

surrendered. This eventually happened, Qaddafi may have thought better of his

ways, and sanctions were lifted in 2003. Meanwhile, Qaddafi had dressed up his

dictatorship with an idiosyncratic political theory. Libya became the "Great

Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya." Jamahiriya, similar to the

Arabic word for "republic," jumhūrīya, was a term coined by Qaddafi for

his political system, which was supposed to be a kind of direct, mass democracy,

but is probably no more democratic than similar arrangements in the Soviet

Union. Like Mao's little red book, Qaddafi produced a little green book. Qaddafi

seems secure enough, like many other dictators (one thinks of Castro), but

increasingly anachronistic (Castro, again).

Libya became a sponsor of terrorism. Blamed for a bombing in Berlin

in 1986, Libya was bombed by Ronald Reagan in retaliation.

Later blamed for a bomb that brought down Pam Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie,

Scotland in 1988, sanctions were imposed on Libya until accused operatives were

surrendered. This eventually happened, Qaddafi may have thought better of his

ways, and sanctions were lifted in 2003. Meanwhile, Qaddafi had dressed up his

dictatorship with an idiosyncratic political theory. Libya became the "Great

Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya." Jamahiriya, similar to the

Arabic word for "republic," jumhūrīya, was a term coined by Qaddafi for

his political system, which was supposed to be a kind of direct, mass democracy,

but is probably no more democratic than similar arrangements in the Soviet

Union. Like Mao's little red book, Qaddafi produced a little green book. Qaddafi

seems secure enough, like many other dictators (one thinks of Castro), but

increasingly anachronistic (Castro, again).

"Romania" means the area in the Balkans and Middle East with successor states to the Mediaeval Roman Empire that was neither part of historic "Francia" (the land of the "Franks" to those in Islām), which means Western, Central, and Northern Europe originally subject to the Latin, Roman Catholic Church in Rome, nor part of historic Russia in Eastern Europe, subject to the Russian Orthodox Church.

This will be an unfamiliar use of the name "Romania" for most, and the reason

for it is explained in "Decadence, Rome and Romania, the

Emperors Who Weren't, and Other Reflections on Roman History," "The Vlach Connection and Further

Reflections on Roman History," and the "Guide and Index to Lists of

Rulers." The double headed eagle of the Palaeologi symbolized the

European and Asian sides of the Empire. This now represents a significant

historical and cultural divide. The Asian side, and the center of the Empire at

Adrianople and Constantinople, is still largely Turkish. This is a rather

different Turkey from the Ottoman Empire, however, secularized and Westernized

by Kemal Atatürk, with things like the Arabic alphabet actually outlawed, now

hoping to join the European Union. On the European side, the successor states to

Rome in the 12th and 13th centuries have reemerged. This is also the case to the

east, where Georgia and

Armenia, kept from the Ottomans  by Russia, are now independent.

by Russia, are now independent.

Thus, "Modern Romania" here means the modern successor states, first to Rome ("Romania" to itself, "Byzantium" to the historians), second to the Ottoman Empire, which in the 14th and 15th centuries established its domination over all former Roman possessions, and more, in the Eastern Mediterranean. As the Roman successors emerged in the 12th century, so do the Ottoman successors emerge in the 19th century. Familiar states from the earlier period are Serbia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, and even Bosnia. The earlier states of the Vlach speaking Romanians, Wallachia and Moldavia, continue from the past, subject to special achievements in Ottoman misrule, ultimately to unite as the modern state of Romānia, the only country in Europe to preserve the proper name of the Roman Empire. Turkey is still the largest and most powerful state in the region.

Entirely new states are Montenegro and Greece itself. Montenegro, the "Black Mountain" (Qara Dagh in Turkish and Crna Gora in Serbo-Croatian), like many remote areas of the Ottoman Empire, began to drift out of central control as Turkish power went into its long decline. "Greece" itself was something that, in a sense, didn't exist in the Middle Ages. What the Ancient Greeks had called themselves, "Hellenes," came to be used in Late Roman times to mean Greek pagans. Greek Christians were "Romans," Rhōmaioi in Greek. This distinction was maintained through the Middle Ages, and was remembered well into the 19th, if not the 20th, century (a Greek can still be Rum in Turkish). A modern Greece, Hellas, that was not an heir to Rome, was an entirely new phenomenon.

The politically, religiously, and culturally dominant language of Mediaeval

Romania was  Greek, whose alphabet today, however, is only used in Greece. For the

same period the

Greek, whose alphabet today, however, is only used in Greece. For the

same period the  Armenian alphabet was in use by Armenians both in Romania and in the

often separate kingdoms of Armenia. Under the Ottomans,

Armenian alphabet was in use by Armenians both in Romania and in the

often separate kingdoms of Armenia. Under the Ottomans,

|

|

||

| Europa | 1. Romania | 2. Constantinople |

| 2. Francia | 1. Rome | |

| 3. Russia | 3. Moscow | |

Georgians dates from the same era as the Armenian, and now continues

to be used in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia. Both the Armenian and the

Georgian alphabets, although based on Greek, have their own striking and

distinctive styles. The conversion of the Slavs resulted in the introduction of

a new alphabet, the

Georgians dates from the same era as the Armenian, and now continues

to be used in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia. Both the Armenian and the

Georgian alphabets, although based on Greek, have their own striking and

distinctive styles. The conversion of the Slavs resulted in the introduction of

a new alphabet, the  Cyrillic, which has remained the alphabet of choice for Slavs who

belong to Orthodox Churches, like the Serbs, Bulgarians, and Russians. When

modern Romanian (Vlach) first began to be written, it also used the Cyrillic

alphabet, but eventually both Romanian and Albanian (also for many centuries

unwritten) were rendered in the

Cyrillic, which has remained the alphabet of choice for Slavs who

belong to Orthodox Churches, like the Serbs, Bulgarians, and Russians. When

modern Romanian (Vlach) first began to be written, it also used the Cyrillic

alphabet, but eventually both Romanian and Albanian (also for many centuries

unwritten) were rendered in the  Latin alphabet, which thus came to be used for spoken languages in

the Balkans for the first time since Latin speaking Roman colonists, and the

Imperial Court in Constantinople, would have used it many centuries earlier.

Since one's alphabet usually went with one's religion in the Middle Ages, the

Turks, and other local converts to Islām, used the

Latin alphabet, which thus came to be used for spoken languages in

the Balkans for the first time since Latin speaking Roman colonists, and the

Imperial Court in Constantinople, would have used it many centuries earlier.

Since one's alphabet usually went with one's religion in the Middle Ages, the

Turks, and other local converts to Islām, used the  Arabic alphabet; and Jews, especially Jews arriving after Spain

expelled them in 1492, used the

Arabic alphabet; and Jews, especially Jews arriving after Spain

expelled them in 1492, used the  Hebrew alphabet. We have already seen some exceptions to the

religion rule, however. Orthodox Christian Churches could be found using

different alphabets, Greek, Armenian, and Cyrillic (as well as, more distantly,

Coptic, Syriac, and Ethiopic), which already had introduced an ethnic or

national dimension to the issue. This is also evident when the Orthodox

Romanians and the largely Moslem Albanians

Hebrew alphabet. We have already seen some exceptions to the

religion rule, however. Orthodox Christian Churches could be found using

different alphabets, Greek, Armenian, and Cyrillic (as well as, more distantly,

Coptic, Syriac, and Ethiopic), which already had introduced an ethnic or

national dimension to the issue. This is also evident when the Orthodox

Romanians and the largely Moslem Albanians

turn to the Latin alphabet, neither with the slightest intention of

entering into religious communion with Papal Roman (i.e. Frankish) Catholicism.

The Turks themselves, directed by Kemal Atatürk, followed suit. The Jews of

Turkey also fell into this, and it became possible to find Ladino, the language

of the 15th century Jewish refugees from Spain, being written in 20th century

Istanbul synagogues using the Turkish version of the Latin alphabet.

turn to the Latin alphabet, neither with the slightest intention of

entering into religious communion with Papal Roman (i.e. Frankish) Catholicism.

The Turks themselves, directed by Kemal Atatürk, followed suit. The Jews of

Turkey also fell into this, and it became possible to find Ladino, the language

of the 15th century Jewish refugees from Spain, being written in 20th century

Istanbul synagogues using the Turkish version of the Latin alphabet.  Thus the ancient prestige of Latin Rome, and the modern

dominance of Latinate Francia, has exerted itself in modern Romania over

Orthodox Christianity, Islām, and Judaism -- even while the old Hebrew alphabet

is now used for Hebrew revived as a spoken language in modern Israel.

Thus the ancient prestige of Latin Rome, and the modern

dominance of Latinate Francia, has exerted itself in modern Romania over

Orthodox Christianity, Islām, and Judaism -- even while the old Hebrew alphabet

is now used for Hebrew revived as a spoken language in modern Israel.

A characteristic of imperial states is an easy mixing of peoples

and languages. They all have too much to fear from the imperial power for too

much trouble to develop between them. When the heavy imperial hand is withdrawn,

however, serious trouble can result. Thus, the end of the British Empire resulted in the

partitions, amid war and massacre, of India, Palestine, and Cyprus. The decline

of Turkish power similarly uncorked more than a century of conflict, continuing

even in 2000, in the Balkans. Border areas end up with the most ambiguous

identities and so can provoke the greatest conflict. Bosnia and

Herzegovina, which had been swapped back and forth between Hungary and

Romania and Serbia in the 12th and 13th centuries, and then were long held by

the Turks, ended up with a mixed population of Croats (Latin/Catholic

Christians), Serbs (Orthodox Christians), and Moslem Bosnians (Bosniacs). All,

as it happened, spoke the same language, Serbo-Croatian, but written in

different alphabets. The disintegration of Yugoslavia, with the lifting of the

heavy imperial hand of Communism in the 1990's, led to terrible fighting,

massacres, and atrocities, most famously carried out by the Serbs against the

others, but not unheard of from the Croatians, Bosniacs, and Kosovar Albanians

also. A famous bridge in Mostar in Herzegovina, which had linked, actually and

symbolically, the Christian and Moslem parts of the city, was destroyed

(evidently by Croatians) in the fighting. With a peace settlement patched up for

Bosnia, the Serbs then turned their hand against the restless Albanian majority

of Kosovo, which the Serbs regarded as the Serbian heartland but which had

contained few Serbs for a long time. It is enough to make one yearn for the

return of the Palaeologi. The first map

above shows the situation in 1817, after the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812,

rebellions by Serbia, and a final grant of autonomy to Serbia. The Ionians

Islands had originally belonged to Venice but were seized by Britain in the

Napoleonic Era and ceded to Britain by the Congress of Vienna.

A characteristic of imperial states is an easy mixing of peoples

and languages. They all have too much to fear from the imperial power for too

much trouble to develop between them. When the heavy imperial hand is withdrawn,

however, serious trouble can result. Thus, the end of the British Empire resulted in the

partitions, amid war and massacre, of India, Palestine, and Cyprus. The decline

of Turkish power similarly uncorked more than a century of conflict, continuing

even in 2000, in the Balkans. Border areas end up with the most ambiguous

identities and so can provoke the greatest conflict. Bosnia and

Herzegovina, which had been swapped back and forth between Hungary and

Romania and Serbia in the 12th and 13th centuries, and then were long held by

the Turks, ended up with a mixed population of Croats (Latin/Catholic

Christians), Serbs (Orthodox Christians), and Moslem Bosnians (Bosniacs). All,

as it happened, spoke the same language, Serbo-Croatian, but written in

different alphabets. The disintegration of Yugoslavia, with the lifting of the

heavy imperial hand of Communism in the 1990's, led to terrible fighting,

massacres, and atrocities, most famously carried out by the Serbs against the

others, but not unheard of from the Croatians, Bosniacs, and Kosovar Albanians

also. A famous bridge in Mostar in Herzegovina, which had linked, actually and

symbolically, the Christian and Moslem parts of the city, was destroyed

(evidently by Croatians) in the fighting. With a peace settlement patched up for

Bosnia, the Serbs then turned their hand against the restless Albanian majority

of Kosovo, which the Serbs regarded as the Serbian heartland but which had

contained few Serbs for a long time. It is enough to make one yearn for the

return of the Palaeologi. The first map

above shows the situation in 1817, after the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812,

rebellions by Serbia, and a final grant of autonomy to Serbia. The Ionians

Islands had originally belonged to Venice but were seized by Britain in the

Napoleonic Era and ceded to Britain by the Congress of Vienna.

My source for the king lists was originally the

Kingdoms of Europe, by Gene Gurney [Crown Publishers, New York, 1982].

Gurney has some errors and obscurities, but I have not found any other work that

has put so much together in one volume. It is a shame that his list of the

Princes of Wallachia and Moldavia is incomplete, but it also looks like it would

be a very long list, since the Turks changed Princes frequently, and in earlier

periods the succession may be imperfectly known. Recent heads of state are

largely from the Regentenlisten und Stammtafeln zur Geschichte Europas by

Michael F. Feldkamp [Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart, 2002]. Feldkamp has a more

complete treatment of Wallachia and Moldavia, but, unfortunately, only prior to

the era shown here. The maps are based on The Penguin Atlas of Recent History

(Europe since 1815) (Colin McEvedy, 1982), The Anchor Atlas of World

History, Volume II (Hermann Kinder, Werner Hilgemann, Ernest A. Menze, and

Harald and Ruth Bukor, 1978), The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia

(John Channon with Rob Hudson, 1995), and various prose histories, such as

The Ottoman Centuries (Lord Kinross, Morrow Quill, 1977).

My source for the king lists was originally the

Kingdoms of Europe, by Gene Gurney [Crown Publishers, New York, 1982].

Gurney has some errors and obscurities, but I have not found any other work that

has put so much together in one volume. It is a shame that his list of the

Princes of Wallachia and Moldavia is incomplete, but it also looks like it would

be a very long list, since the Turks changed Princes frequently, and in earlier

periods the succession may be imperfectly known. Recent heads of state are

largely from the Regentenlisten und Stammtafeln zur Geschichte Europas by

Michael F. Feldkamp [Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart, 2002]. Feldkamp has a more

complete treatment of Wallachia and Moldavia, but, unfortunately, only prior to

the era shown here. The maps are based on The Penguin Atlas of Recent History

(Europe since 1815) (Colin McEvedy, 1982), The Anchor Atlas of World

History, Volume II (Hermann Kinder, Werner Hilgemann, Ernest A. Menze, and

Harald and Ruth Bukor, 1978), The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia

(John Channon with Rob Hudson, 1995), and various prose histories, such as

The Ottoman Centuries (Lord Kinross, Morrow Quill, 1977).

The two maps, just above and to the right, show the situation (1) after the War of Greek Independence (1821-1829) and (2) after the Crimean War (1853-1856). To save Greece, all the Great Powers were drawn in against Turkey.

With Greek independence went increased territory for Serbia, autonomy for Wallachia and Moldavia, and border concessions to Russia.

In the Crimean War, Britain and France joined Turkey against Russia, with

much of the fighting taking place, as one might expect from the name, in the

Crimea. This pretty much preserved the status quo for Turkey, though the borders

were extended against Russia along the Black Sea. One change we see, however,

was the unification of Wallachia and Moldavia into the state of Romānia.

| 1. ROMĀNIA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continued from "Rome and Romania," "Romanians" | |||

| WALLACHIA | MOLDAVIA | ||

| Radu Mihnea | Voivode, Prince, Governor, 1611-1616, 1623-1626 | ||

| Leon Tomsa | 1629-1632 | Miron Barnovschi Movila |

Voivode, Prince, Governor, 1626-1629, 1633 |

| Matei Basarab | 1632-1654 | Vasie Lupu | 1634-1653 |

| Constantine Serban |

1654-1658 | ||

| Grigore Ghica | 1660-1664 | ||

| Serban Cantacuzino |

1678-1688 | ||

| Constantine Brancoveeanu |

1688-1714 | Constantine Cantemir |

1685-1693 |

| Phanariot Greek Tax Farming | |||

| 1716-1717, 1719-1730 |

Nicholas Mavrocordat | 1711-1714 | |

| Stephen Cantacuzino |

1714-1716 | ||

| 1741-1744 | Michael Racovita | 1717-? | |

| 1735-1741, 1744-1748 |

Gregoy Ghica | 1726-1733, 1774-1777 | |

| Constantine Mavrocordat | 1741-1743, ?-1769 | ||

| Russian right of

intervention, Treaty of Kuchuk Karinarji, 1774 | |||

| Alexander Ypsilanti |

1774-1782 | Alexander Moruzi |

?-1806 |

| Constantine Ypsilanti |

1802-1806 | ||

| Russian Occupation, 1806-1812 | |||

| John Caragea | 1812-1818 | Scarlat Calimah | 1812-1819 |

| Alexander Sutu | 1818-1821 | ||

| Russian Occupation,

1828-1834; Governor Count Kisselev | |||

| Alexander Ghica | 1834-1842 | Mihai Sturdza | 1834-1849 |

| Georghe Bibescu | 1842-1848 | ||

| Revolution in Wallachia, 1848; Russian Occupation, 1848-1851; Crimean War, 1853-1856; Russian Occupation, 1853-1854; Austrian Occupation, 1854-1857 | |||

| Alexander John Cuza of Moldavia | 1859-1866 | ||

| Charles Eitel Frederick of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, Carol I |

1866-1881 | ||

| King, 1881-1914 | |||

| Russo-Turkish War, 1876-1878; Russian Invasion, Romania proclaimed independent, 1877; Congress of Berlin, Romania Independent, 1878 | |||

| Ferdinand | 1914-1927 | ||

| Michael | 1927-1930, 1940-1947 | ||

| Carol II | 1930-1940 | ||

| Ion Antonescu, pro-German dictator | 1940-1944 | ||

| Communist takeover, 1947 | |||

| Constantin Parhon | President, 1948-1952 | ||

| Petru Groza | 1952-1958 | ||

| Ion Georghe Maurer | 1958-1961 | ||

| Georghe Georghiu-Dej | 1961-1965 | ||

| Chivu Stoica | 1965-1967 | ||

| Nicolae Ceauēescu | 1967-1989, executed | ||

| Ion Iliescu | 1989-1996, 2000-present | ||

| Emil Constantinescu | 1996-2000 | ||

The Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia have a continuous

institutional history back to the 14th Century, which means that this table

simply continues the table begun on the Rome and Romania page.  Turkish rule, however, led to the practice of the appointment of

Greek tax farmers, the Phanariots (from the Phanar section of Istanbul), as

Princes. Their job was simply to get as much money out of the land as possible,

both for the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman government) and for themselves (the

reason to be a tax farmer). This was not good, or popular, for the

Principalities, but not much could be done about it until Russian power began to

be felt in the region. The Russian wars against Turkey in the 19th Century led

several times to the occupation of Wallachia and Moldavia. After the Crimean War

(18453-1856) and, for a change, Austrian occupation (1854-1857), and a bad

experience with a local candidate for rule of the unified country, a European

prince, as in Greece and Bulgaria,

Turkish rule, however, led to the practice of the appointment of

Greek tax farmers, the Phanariots (from the Phanar section of Istanbul), as

Princes. Their job was simply to get as much money out of the land as possible,

both for the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman government) and for themselves (the

reason to be a tax farmer). This was not good, or popular, for the

Principalities, but not much could be done about it until Russian power began to

be felt in the region. The Russian wars against Turkey in the 19th Century led

several times to the occupation of Wallachia and Moldavia. After the Crimean War

(18453-1856) and, for a change, Austrian occupation (1854-1857), and a bad

experience with a local candidate for rule of the unified country, a European

prince, as in Greece and Bulgaria,  was brought in, Karl of Hohenzollern. The Congress of Berlin

recognized Karl (Carol) and Romanian independence (1878). With the Allies in

World War I, winning Transylvania from Hungary and Moldova from Russia --

Romania was the biggest long term winner of the War in the Balkans -- Romania,

after much internal strife, switched to the Axis in World War II, losing Moldova

to the Soviet Union (seized in 1940, actually, before Romania was a belligerent)

and part of Dobruja to Bulgaria. While Moldova is now independent, I have not

noticed any discussion of reunion with Romania.

was brought in, Karl of Hohenzollern. The Congress of Berlin

recognized Karl (Carol) and Romanian independence (1878). With the Allies in

World War I, winning Transylvania from Hungary and Moldova from Russia --

Romania was the biggest long term winner of the War in the Balkans -- Romania,

after much internal strife, switched to the Axis in World War II, losing Moldova

to the Soviet Union (seized in 1940, actually, before Romania was a belligerent)

and part of Dobruja to Bulgaria. While Moldova is now independent, I have not

noticed any discussion of reunion with Romania.

Rejecting the Cyrllic alphabet and the Turkish influenced "Rumania" (or

"Roumania") for  the Latin alphabet and the pure Latin Romānia, Romania can

now claim that name as its own, with few remembering that it was the proper name

of the Roman (and the "Byzantine") Empire. In the Middle Ages, "Romania" tended

to refer to the contemporaneous extent of the Empire, i.e. Anatolia and the

Balkans ("Asia and Europa" or "Rūm and Rumelia"). The modern state might be said

to be "Lesser Romania" in contrast to that "Greater Romania"; but this might be

considered insulting by Romanians (though intentionally no more so than "Lesser Armenia" in

Cilicia) and so is not likely to catch on.

the Latin alphabet and the pure Latin Romānia, Romania can

now claim that name as its own, with few remembering that it was the proper name

of the Roman (and the "Byzantine") Empire. In the Middle Ages, "Romania" tended

to refer to the contemporaneous extent of the Empire, i.e. Anatolia and the

Balkans ("Asia and Europa" or "Rūm and Rumelia"). The modern state might be said

to be "Lesser Romania" in contrast to that "Greater Romania"; but this might be

considered insulting by Romanians (though intentionally no more so than "Lesser Armenia" in

Cilicia) and so is not likely to catch on.

The mysterious history of Romance speakers in the Balkans, the Romanians and

Vlachs, whose existence is not noticed until the 12th Century and whose language

is not attested until the 16th, is treated separated in "The Vlach Connection and Further

Reflections on Roman History." This is a story now charged with the

nationalism both of Romania and neighbors like Hungary.

The marriages of the Romanian Royal Family quickly connected it to

major European, especially British and Greek, royalty. Thus King Ferdinand was

the grandson of a first cousin of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (Ferdinand of

Portugal, the brother of Augustus, Prince of Coburg, who was the father of

Ferdinand of Bulgaria),

and he married one of their own granddaughters, Marie of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. King

Carol II then married Helen of Greece, who was a

great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria, through her mother Sophia, the sister of

Kaiser Wilhlem II of Germany. All these

connections, of course, profited the monarchy little in the conflicts of fascism

and communism that had the country under one form of dictatorship or another

from 1940 to 1989.

The marriages of the Romanian Royal Family quickly connected it to

major European, especially British and Greek, royalty. Thus King Ferdinand was

the grandson of a first cousin of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (Ferdinand of

Portugal, the brother of Augustus, Prince of Coburg, who was the father of

Ferdinand of Bulgaria),

and he married one of their own granddaughters, Marie of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. King

Carol II then married Helen of Greece, who was a

great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria, through her mother Sophia, the sister of

Kaiser Wilhlem II of Germany. All these

connections, of course, profited the monarchy little in the conflicts of fascism

and communism that had the country under one form of dictatorship or another

from 1940 to 1989.

The two maps above show the situation before and after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. Note that by then Britain had ceded the Ionians Islands to Greece (1864). In 1875 rebellions started in Bosnia and then Bulgaria. The brutality with which these were suppressed aroused European opinion, and after some delay Russia declared war. With some hard fighting, the Russians ended up capturing Adrianople and arriving at the outskirts of Constantinople. The Treaty of San Stephano which ended the war mostly freed the Balkans, but the Great Powers didn't like it. The Congress of Berlin rolled things back a bit. Serbia, Romānia, and Montenegro all became independent, with increases in territory, but Bulgaria was divided and merely allowed autonomy. Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Novipazar were made protectorates of Austria. The map looked much the same for many years, with Bulgaria annexing East Rumelia in 1885.

| 2. MONTENEGRO | |

|---|---|

| Danilo I Petrovic | Prince-Bishop, 1697-1737 |

| Sava | 1737-1756 d.1782 |

| Vasili | Coadjutor, 1756-1766 |

| Stephen the Little |

Coadjutor, 1766-1774 |

| Sava | Coadjutor, 1774-1782 |

| Peter I | 1782-1830 |

| Peter II | 1830-1851 |

| Danilo II | 1851-1860 |

| Nicholas | 1860-1910 |

| King, 1910-1918, d.1921 | |

| Union with Yugoslavia,

1918; Independent, 3 June 3 2006 | |

| Filip Vujanovic | President, 2006-present |

Serbia's only access to the sea, through the historic port of Kotor

(Cattaro in Italian, obtained from Austria after World War I), the fear is that,

should the Montenegrans decide to go their own way, the Serbs would use force,

with enough local support to make resistance abortive.